A serial CEO thinks about why he does it.

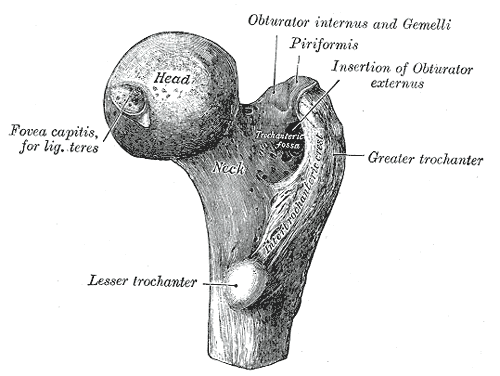

Trochanter!” Harry said, leaning across the dark wood of the bar where we’d met for lunch. We hadn’t seen each other for a year, so when Harry saw my crutch he wanted to know what I’d done to get it. I told him about the bike, the dark, the last patch of ice at the end of winter, and the light came up in his eyes as he sketched out bones on a napkin to find out where, exactly, I’d broken my hip.

“That was one of my very first projects,” Harry explained. The client was a big healthcare company that saw a market opportunity in designing ways to keep older people from breaking their hips. The tricky part, Harry explained, was testing. They’d developed a prototype you’d wear inside your pants, a pad with a hard shell on the outside that shifted the impact away from the point of your pelvic bone. But you couldn’t go around pushing over older people to see if your new product actually worked. “Cadavers,” he said. “We’d drop them like they were falling.”

Harry used to run the design firm where I’d worked, and then he’d left to help lead another company, and when we met, he was just done with another CEO gig. The non-compete he’d signed was expiring soon, Harry explained, and he was wondering which he wanted more: to keep working as an independent consultant — or to take on another leadership role.

I asked Harry if he thought he’d be able to stay away from the C-suite, if he wouldn’t miss it. I thought he’d say something about creative freedom, or the power to make a real impact. (I didn’t figure Harry would mention status, since I’d seen the nothing-special desk he’d chosen in the middle of our open office, and I’d once heard from a client how he was the only CEO they’d ever met in work boots, while he was building a prototype bank branch out of foamcore.) But the thing that Harry said he’d miss was responsibility.

It seemed like a strange choice. Responsibility is what most of us spend a lot of time trying to avoid. We look at kids on the playground and talk about how lucky they are to have no work that needs to get done; nobody they need to make happy; nowhere they need to get on time.

But Harry was never much for the obvious answer, and he got me thinking about Robert Frost’s poem, “Birches.” The speaker imagines himself a young boy, swinging from branches out into the sky, escaping the ordinary world and all its worries. But no matter how “weary of considerations” he gets, the speaker insists he doesn’t want to get away for good. “Earth’s the right place for love,” he says, not because it’s perfect, but because it’s the only chance we get to make things happen. “I’d like to get away from earth awhile / And then come back to it and begin over.”