Last night, my daughter asked for Harold and the Purple Crayon for her bedtime story.

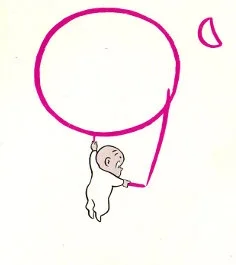

For those of you who may not have read it for a while, or might never have, the book starts with a young boy deciding to take a walk in the moonlight. He steps onto the next page, which is empty except for Harold in his footie pajamas, holding a crayon in his hand. He draws a moon to make the moonlight and a long, straight path to walk along under it. “And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him.”

Though we’d read the story many times before, this was the first time my daughter asked “How come there’s nothing in the world except for what he draws?

And as we talked about why, and then watched the story unspool—watched Harold draw a tree and the apples on it, and because they look so tempting, a dragon underneath to guard it; an ocean and a boat to sail across it; the pies he’s hungry for and a moose to eat the parts that he can’t finish—I thought how well this bedtime story captured what so many progressive schools struggle to say about themselves.

When people ask school-folk what they mean when they call themselves “progressive,” they're sometimes unsure of where to look for answers. Is it in the way their students call teachers by their first names, or in the fact that they cast votes with the rest of the trustees? Are progressive schools different because their courses are more focused, or because of how much responsibility they give students in shaping those courses? I think these things matter a great deal, but the list they’re part of just keeps going. I think that somewhere underneath it there’s a simpler story we can tell: a myth, perhaps, that might catch hold of what we want our students to believe about the world and their place in it.

By the material we make our courses out of and the way we ask students to speak for themselves, we teach them a basic orientation toward the world, a faith that all those facts that fill our day-to-day—the old furniture wrapped in plastic covers, the landscape that has been leveled already and mapped out in familiar streets and avenues—might still be re-imagined and made better. We want our students to grow up in the conviction that they could always get back to the drawing board. We want them to know how to close their eyes and erase, for a moment, all those hard facts that frame the limits of what might they might do next.

We want our children to know, deeply and in its details, the world they’ve been given—its history and literature and the art that was made long before any of them ever stood in front of a canvas. But, in a certain sense, we don’t want them to “believe” in it. We don’t want them simply to accept what they’ve been given as though it were the inevitable last word; we don’t want them to feel that they come after everything important has already been figured out and finalized. We want them to approach all this glorious stuff not like a tourist walking through a museum but like an artist walking through another artist’s studio: we want them able to appreciate what’s true and beautiful because they know how to make it.

“And he set off on his walk, taking his big purple crayon with him.”

Set up a complimentary consultation.